Last Updated on September 16, 2022

Has this hate become a symptom or a deeper problem? How did it get this far? Is this a small problem or a sign of a bigger problem? How did we let it get so common? We have all been affected by hatred, but when did it become so ordinary? And what can we do to make it less common? This article explores these questions and more. It may help you understand the real issue.

Is it a symptom of a larger problem?

If you are a medical doctor who specializes in public health, you might wonder: Is hate a symptom of broader issues? As an infectious disease, it spreads through a person’s mind, manifesting as violence, fear, and ignorance. As a public health problem, hatred needs to be treated as such, with preventative measures in place for a limited health-care budget.

A study by Zayas and Shoda found that people who harbor hatred are often deeply flawed, lacking self-esteem, or fear of change. A student may use their teacher as a stand-in for frustration with academia, spreading rumors and vicious email. Further, prolonged hatred might lead to preemptive action against the person who incited the feelings. As a result, some people choose to let hatred fester unchecked and act violently.

One recent study found that a majority of 18-to-25-year-olds had experienced online hate within the past three months. In the last five years, research has shown that hate is often manifested in microaggressions, which are less serious but equally harmful. Recent studies have also shown that up to one-in-four Black and Latinx students experienced racial microaggressions. But the data are probably underestimated due to underreporting.

The rise of hate-motivated behaviors is one of the most pressing issues facing public health. Hateful behavior impacts mental and physical health, early death, social isolation, and inadequate health care. These effects extend beyond the victim, including structural inequalities. While there are a growing number of interventions targeting hateful behavior, the evidence pointing toward preventive strategies is insufficient. In order to prevent such incidents, multilevel research and prevention programming design is needed.

Hate is a common cause of many violent conflicts around the world. It also produces byproducts such as stress, depression, and anxiety. Marshall Marinker, a psychiatrist in La Jolla, CA, described disease as a pathological process that is undetermined in its origins. Moreover, he suggests that hatred is a mental illness, rather than a physical disease.

In order to prevent these crimes, the victims need to learn to identify the source of hate and to resist it. This can be done by creating a diverse coalition of diverse people who can help fight hate. These coalitions can include children, media, police, and community organizations. The coalitions can stand up to organized hate groups, educate the public, and repair any vandalism caused by hate.

Campus administrators are struggling to mitigate the harmful effects of online hate speech while maintaining the First Amendment rights of students. Assessment is one step toward addressing these challenges. It must assess the vulnerability of marginalized communities on college campuses. Unfortunately, current methods of assessment are heavily limited. Most existing reports are anecdotal and based on discrete events. In addition to identifying the source of hate speech, they often do not include the root causes of the problem.

In the long run, hate incidents must be counteracted by acts of goodness. Silence is also deadly in the face of hate. Silence may be interpreted as acceptance from the hate group’s perpetrators or victims. Hate rips society apart along racial, ethnic, gender, and religious lines, causing riots, civil disturbances, and other violent acts. Ultimately, hate groups are anti-democratic.

Is it a sign of a deeper problem?

When you experience hatred, you may think that the cause is a personal one, but that is not true. Hate is a problem if it grows and festers, taking a toll on your soul and spirit. You can change the hatred in yourself, but changing the people around you must be an equally important step. You can’t let hatred dominate your life and ruin your future.

Hatred feelings can manifest as a symptom of deeper problems in relationships, and can also cause physical problems. The brain’s chemistry changes when we feel angry, and it triggers our “fight or flight” responses. In addition, our autonomic nervous system is stimulated, which increases the stress hormones cortisol and adrenalin, and depletes our adrenals. These hormones can cause chronic illness, weight gain, and even a host of other negative side effects.

A recent study by Jack Levin shows that haters are usually underachieving people with a deeply held inferiority complex. These individuals latch onto the achievements of others and associate with those accomplishments. It is this association that causes them to become violent. This is what fuels hate crimes. If we can’t relate to our fellow human beings, we will feel justified in acting violently against them.

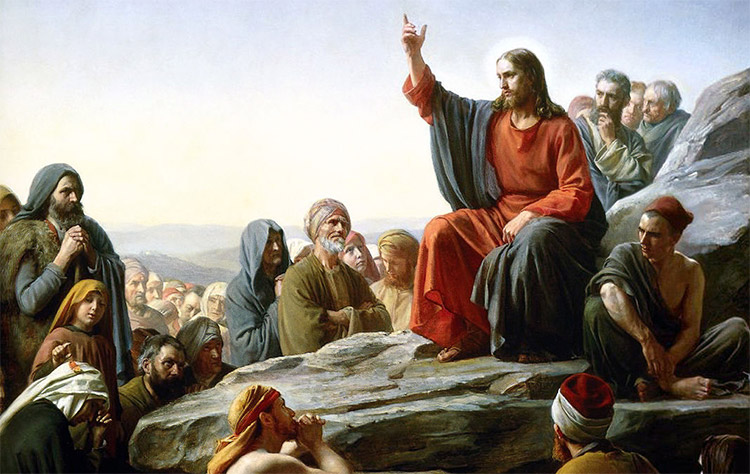

A recent study published in Science magazine suggested that Christians should not use hate as a way to get people to change their attitudes. This study, however, suggests that Christians should learn more about the history of hate and why it develops. For example, Christianity has argued that loving others is the best motivation, but in practice, Christians have been accused of devaluing the beliefs of non-believers. In addition to devaluing non-believers and repressing their culture, Christianity has contributed to this phenomenon.

In addition to speaking out against hate crimes, it is important to reach out to allies to build a stronger, more diverse community. For example, you can build a coalition of community members, including churches, police, and women’s groups. When you have a diverse coalition of people, you’ll be able to stand up to organized hate groups, isolate them, and educate others about the hateful practices that fuel them.

Hate groups have spread propaganda and demonized various groups. They spread conspiracy theories and false propaganda to frighten the public and silence opposition. Yet, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, fewer than five percent of hate crimes are committed by hate groups. Most of them are perpetrated by young males acting on their own, or in small groups. These youths often have very little political or social knowledge, and their motives are often influenced by dehumanizing propaganda and music.

Whenever you feel hatred for another person, ask yourself why you feel that way. Usually, it stems from an underlying fear or insecurity. And since hate feeds itself, it builds up and fuels further hatred. If you’re unable to answer that question, take a break and try to find the source of your hatred. Try meditation or meditate to relax your mind. By becoming calm and centered, you’ll be able to better control your emotions.

When you feel hatred, you may want to look into your environment. For instance, if you had a horrible teacher, you might want to make sure that the teacher’s reputation was good. Similarly, if you’ve been bullied in school, you might feel resentment towards your teacher. That’s a dangerous situation and should be treated with caution. This is not an easy task, but it’s a good starting point.

About The Author

Gauthier Daniau is a freelance problem solver. He first discovered his knack for trouble-shooting when he was still in diapers - and hasn't looked back since. When he's not slaying zombies or internet ninjas, GAUTHIER enjoys working with animals of all shapes and sizes. He's also something of a social media expert and loves to get lost in numbers and figures.