Last Updated on July 27, 2023

Welcome to our article on the fascinating topic of Mexico’s independence from Spain. In this piece, we will delve into the historical events that led to Mexico’s liberation, the key figures who played pivotal roles, and the challenges faced by the newly independent nation. We will also explore the impact of Mexico’s independence on other Latin American countries and the subsequent evolution of its political system. Additionally, we will examine the socioeconomic changes that occurred in post-independence Mexico. By the end of this article, you will have a comprehensive understanding of the timeline and significance of Mexico’s struggle for independence. So, let’s embark on this enlightening journey together!

Background on Mexico’s colonization by Spain

Mexico’s colonization by Spain began in the early 16th century when Spanish conquistadors arrived in the region. Here are some key points about the background of Mexico’s colonization:

- Spanish conquistadors, led by Hernan Cortes, conquered the Aztec Empire in 1521, establishing the colony of New Spain.

- The Spanish brought with them diseases, such as smallpox, which devastated the indigenous population.

- The Spanish imposed their language, religion, and culture on the native people, leading to the assimilation and acculturation of the indigenous population.

- The Spanish exploited Mexico’s resources, particularly silver mines, which fueled the Spanish economy.

- Mexico became a major hub for trade between Europe, Asia, and the Americas, leading to the growth of cities and the development of a mixed-race population.

Overall, Mexico’s colonization by Spain had a profound impact on the country’s history, culture, and identity.

Causes of the Mexican War of Independence

The Mexican War of Independence was a significant event in the history of Mexico, marking the country’s liberation from Spanish rule. The causes of this war can be traced back to several factors that had been brewing for years. One of the main causes was the oppressive rule of the Spanish colonial government, which imposed heavy taxes and restrictions on the Mexican population. This led to widespread discontent and a desire for change among the Mexican people.

Another cause of the war was the influence of the Enlightenment ideas that were spreading throughout Europe and the Americas during the 18th century. These ideas emphasized the importance of individual rights and freedom, which resonated with many Mexicans who were tired of living under Spanish control.

Additionally, the French Revolution and the American Revolution served as inspirations for the Mexican independence movement. The success of these revolutions showed that it was possible for colonies to break free from their colonial masters and establish their own governments.

Overall, a combination of economic, political, and ideological factors contributed to the outbreak of the Mexican War of Independence. This war would ultimately lead to Mexico’s independence from Spain and the establishment of a new nation.

Key events and leaders during the war

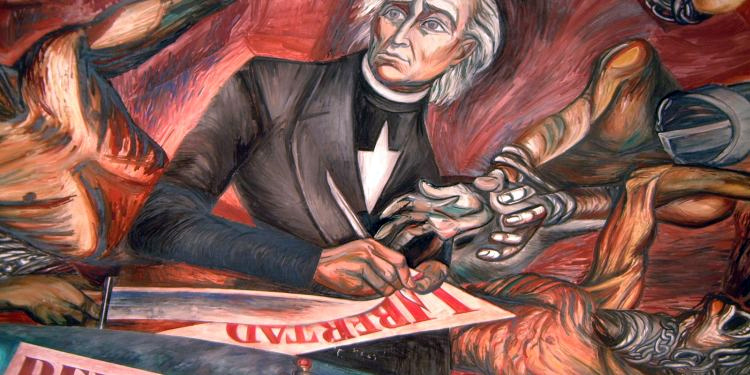

The Mexican War of Independence was a long and arduous struggle that lasted from 1810 to 1821. Throughout this period, there were several key events and leaders that played a crucial role in the fight for independence.

Hidalgo’s Grito de Dolores

One of the most significant events was the Grito de Dolores, or the Cry of Dolores, which took place on September 16, 1810. It was during this event that Miguel Hidalgo, a Catholic priest, called for the people of Mexico to rise up against Spanish rule. This marked the beginning of the war and ignited a sense of patriotism and unity among the Mexican people.

Morelos’ leadership

Another important leader during the war was José María Morelos. He was a military strategist and a skilled leader who played a crucial role in organizing and leading the Mexican forces. Morelos was known for his determination and his ability to inspire his troops, which helped to keep the fight for independence alive.

Iturbide and the Plan of Iguala

One of the turning points in the war was the Plan of Iguala, proposed by Agustín de Iturbide. This plan called for the establishment of an independent Mexico, with a constitutional monarchy led by a European prince. Iturbide’s leadership and the support of the military were instrumental in achieving victory and ultimately securing Mexico’s independence.

These key events and leaders played a crucial role in the Mexican War of Independence, shaping the course of history and paving the way for a new era of independence and self-governance in Mexico.

Declaration of Independence and establishment of the First Mexican Empire

After years of fighting and struggle, Mexico finally declared its independence from Spain on September 27, 1821. This declaration marked the establishment of the First Mexican Empire, with Agustín de Iturbide as its first emperor.

- The declaration of independence was a significant moment in Mexican history, as it marked the end of Spanish colonial rule and the beginning of a new era for the country.

- Iturbide, a former Spanish officer who had switched sides to support the independence movement, played a crucial role in the establishment of the empire.

- The First Mexican Empire was short-lived, lasting only two years. It faced numerous challenges, including political instability and opposition from various factions.

- In 1823, Iturbide was overthrown, and Mexico transitioned to a federal republic.

The declaration of independence and the establishment of the First Mexican Empire were significant milestones in Mexico’s history, symbolizing the country’s newfound freedom and its aspirations for self-governance. However, the challenges faced by the newly independent Mexico were far from over.

Challenges faced by the newly independent Mexico

After gaining independence from Spain, Mexico faced numerous challenges that hindered its progress and stability. These challenges included:

- Political instability: The transition from a colony to an independent nation was not smooth, leading to political instability. Different factions and leaders emerged, each vying for power and control.

- Economic struggles: Mexico’s economy was heavily dependent on Spain during the colonial period. With independence, the country had to establish its own economic system, which proved to be a difficult task. The lack of infrastructure, limited resources, and economic policies hindered Mexico’s economic growth.

- Foreign intervention: Mexico faced foreign intervention from various countries, including Spain, France, and the United States. These interventions further destabilized the country and hindered its progress.

- Social unrest: The Mexican society was divided along various lines, including class, race, and regional differences. These divisions led to social unrest and conflicts, making it challenging for the newly independent Mexico to establish a unified society.

- Border disputes: Mexico had to deal with border disputes with neighboring countries, particularly the United States. These disputes led to conflicts and territorial losses for Mexico.

- Legacy of colonialism: The legacy of Spanish colonialism, including social hierarchies and unequal distribution of wealth, continued to persist even after independence. Overcoming these deep-rooted issues proved to be a significant challenge for Mexico.

Despite these challenges, Mexico persevered and gradually worked towards stability and progress in the years following its independence.

Impact of Mexico’s independence on other Latin American countries

Mexico’s independence from Spain had a profound impact on other Latin American countries, inspiring movements for independence throughout the region. The success of Mexico’s struggle for independence served as a catalyst for other countries to seek their own freedom from Spanish colonial rule.

One of the most significant impacts of Mexico’s independence was the spread of revolutionary ideas and the formation of alliances among Latin American countries. The Mexican War of Independence demonstrated that it was possible for a colony to successfully break free from its colonial power, inspiring other nations to follow suit.

Furthermore, Mexico’s independence led to the weakening of Spanish control over its colonies in the Americas. As other countries in the region gained their independence, Spain’s grip on its colonial territories loosened, ultimately leading to the collapse of the Spanish Empire in the Americas.

In addition, Mexico’s independence served as a model for other countries in terms of establishing their own political systems and institutions. The Mexican Declaration of Independence and the establishment of the First Mexican Empire provided a blueprint for other nations to follow in their quest for self-governance.

In conclusion, Mexico’s independence from Spain had a far-reaching impact on other Latin American countries, inspiring movements for independence and leading to the weakening of Spanish colonial control in the region. The success of Mexico’s struggle for independence served as a beacon of hope for other nations, igniting a wave of revolutionary fervor throughout Latin America.

Evolution of Mexico’s Political System After Independence

After gaining independence from Spain, Mexico underwent significant changes in its political system. The country transitioned from a monarchy to a republic, with various forms of government being implemented over the years.

First Mexican Empire

Following independence, Mexico established the First Mexican Empire under the leadership of Agustín de Iturbide. However, this empire was short-lived and faced numerous challenges, leading to its collapse in 1823.

Republicanism and Federalism

After the fall of the First Mexican Empire, Mexico adopted a republican form of government. The country experimented with different political systems, including federalism, where power was divided between the central government and individual states.

Centralism and Dictatorship

In the mid-19th century, Mexico experienced a period of centralism and dictatorship. Leaders such as Antonio López de Santa Anna held significant power and ruled with an iron fist, suppressing opposition and limiting democratic processes.

Constitutional Reforms

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Mexico underwent constitutional reforms aimed at establishing a more democratic and stable political system. These reforms included the adoption of a new constitution in 1917, which introduced social and labor rights.

Modern Political System

Today, Mexico operates as a federal republic with a multi-party system. The country has made significant progress in strengthening its democratic institutions and promoting political participation.

In conclusion, Mexico’s political system has evolved significantly since gaining independence from Spain. From the establishment of the First Mexican Empire to the adoption of a republican form of government, Mexico has experienced various political changes throughout its history.

Socioeconomic changes in post-independence Mexico

After gaining independence from Spain, Mexico experienced significant socioeconomic changes that shaped the country’s future. One of the most notable changes was the abolition of slavery in 1829, which marked a major shift in the country’s labor system. This decision was influenced by the ideals of the Mexican War of Independence, which emphasized equality and freedom.

Another important change was the redistribution of land. The newly independent Mexico sought to address the issue of land ownership, which had been heavily concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy individuals. Land reforms were implemented to distribute land more equitably among the population, with the aim of reducing social inequality.

Industrialization also played a crucial role in post-independence Mexico. The country saw the emergence of new industries, such as textile manufacturing and mining, which contributed to economic growth and job creation. This led to urbanization as people migrated from rural areas to cities in search of employment opportunities.

However, despite these changes, Mexico still faced numerous challenges in its socioeconomic development. The country struggled with political instability, corruption, and economic inequality, which hindered its progress. It would take several decades and ongoing reforms for Mexico to address these issues and achieve sustained economic growth.

In conclusion, the post-independence period in Mexico was characterized by significant socioeconomic changes, including the abolition of slavery, land redistribution, and industrialization. These changes laid the foundation for Mexico’s future development, but also presented challenges that would need to be addressed in the years to come.

After examining the history of Mexico’s independence from Spain, it is clear that this event had a profound impact on the country and the region as a whole. The Mexican War of Independence was a result of various causes, including social inequality and political unrest. The war itself was marked by key events and leaders who fought for the country’s freedom.

The Declaration of Independence and the establishment of the First Mexican Empire were significant milestones in Mexico’s journey towards independence. However, the newly independent Mexico faced numerous challenges, including political instability and economic struggles.

Mexico’s independence also had a ripple effect on other Latin American countries, inspiring movements for independence throughout the region. The evolution of Mexico’s political system after independence further shaped the country’s future.

Furthermore, post-independence Mexico experienced significant socioeconomic changes, as the country sought to rebuild and redefine itself.

In conclusion, Mexico’s independence from Spain was a pivotal moment in its history, with far-reaching consequences. It marked the beginning of a new era for Mexico and served as an inspiration for other nations in their fight for freedom. The challenges faced by Mexico in the aftermath of independence shaped its trajectory and set the stage for its future development.

Discover the historical significance of Mexico’s independence from Spain and its impact on Latin America.

About The Author

Alison Sowle is the typical tv guru. With a social media evangelist background, she knows how to get her message out there. However, she's also an introvert at heart and loves nothing more than writing for hours on end. She's a passionate creator who takes great joy in learning about new cultures - especially when it comes to beer!