Last Updated on September 17, 2022

If you want to learn how to build a larynx, there are some basics you must know. This article will cover the Cuneiform cartilages, Epiglottis, Vocal folds, and the Right recurrent laryngeal nerve. Then you can build a larynx in your imagination. But before you go too far, read this article and understand what these structures do.

Vocal folds

The vocal folds are the layers of tissue that cover the mucosa. This mucosa is covered by a thin epithelium, which can take many shapes. The vocal folds are multilayered, able to stretch and contract, and can withstand varying amounts of impact. During phonation, these structures vibrate to produce the sound we make. As a result, they are flexible, and they can also be stretched and contracted to provide different levels of sound.

The vocal folds are made up of a highly specialized combination of ligament, muscle, and mucosa. The ligament is particularly interesting because it is capable of bearing significant pressure while phonating over a broad range of notes. They can be represented by a thin pink line. These folds help to produce the sound that you need to produce. This is the reason they are so important.

The vocal folds are attached to the thyroarytenoid muscle, which shortens them and pulls them toward the thyroid end. The vocal folds are attached to a series of tiny muscles, called arytenoids, that provide support for the vocal cords. They also help to maintain the larynx’s glottic closure. These muscles are important for a proper functioning larynx.

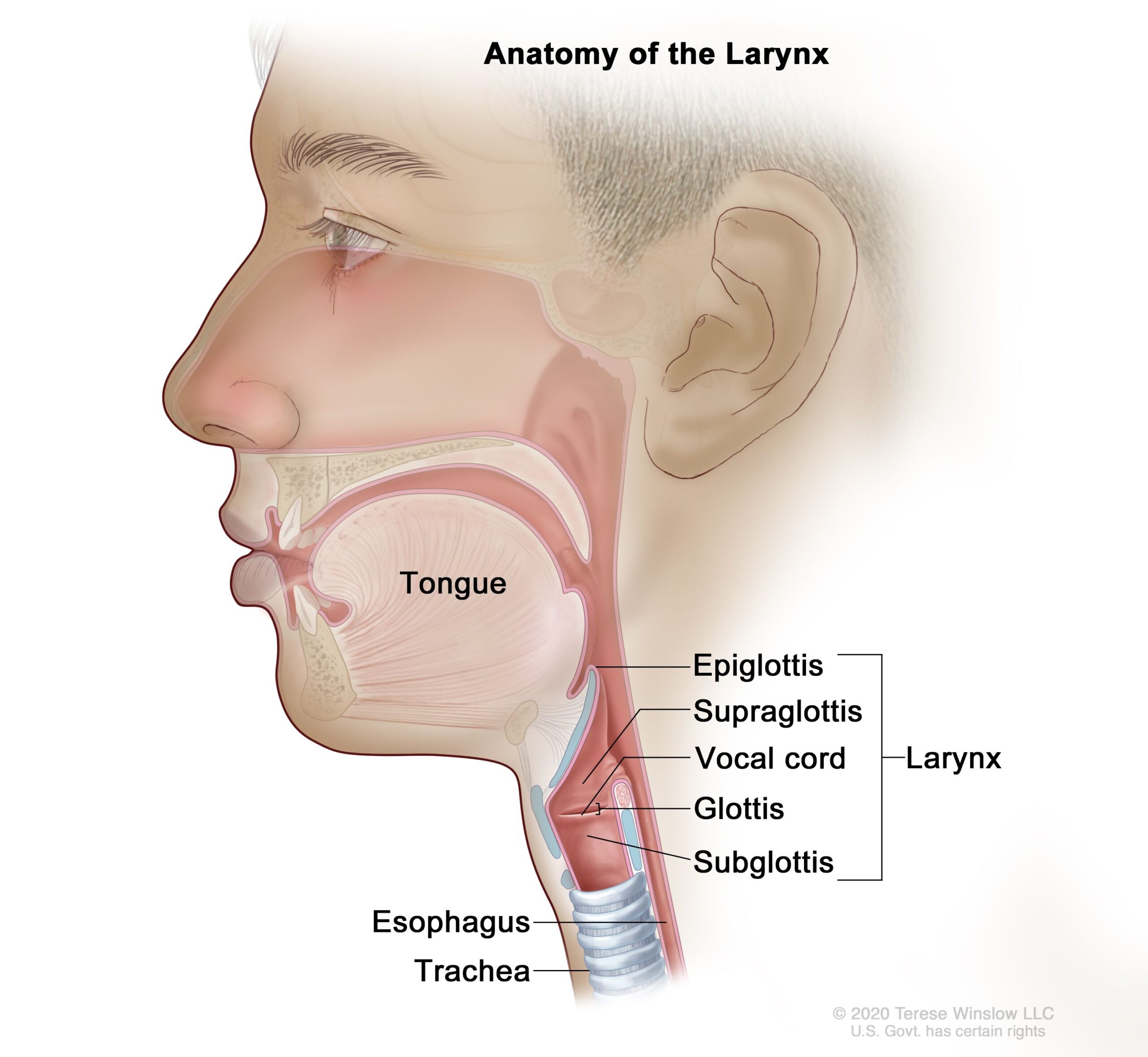

The voice box is comprised of three main parts: the glottis, the vocal folds, and the tongue. Each component of the larynx plays a specific role in producing the voice. In addition, the diaphragm and abdominal and chest muscles help coordinate airflow into and out of the lungs. The vocal folds are multilayered and contain muscles, which are covered with mucus. Between the folds is a space called the glottis, which closes and opens during vocal fold movement.

Cuneiform cartilages

There are nine cuneiform cartilages in the larynx, and only three of them are paired and bilaterally symmetrical. These cartilages are crucial for accurate larynx building, and their placement is vital to the function of the voice box. They make up the front portion of the larynx, where the vocal cords are located.

The cricoid lamina articulates with the arytenoid cartilage. The arytenoid cartilages form a complex system, including apex, cricoid ring, vocal fold attachment, muscular process, and lateral cricoid. The lateral cricoid muscle moves the vocal folds and closes the rima glottidis during abduction and adduction.

The larynx begins to form during the fourth week of development, and the primitive pharynx and foregut are merged. The fourth and fifth branchial arches are the sources of corniculate and thyroid cartilages, and the sixth archial arch merges with the fourth. The fifth branchial arch is involved in corniculate cartilage formation, but it is degenerate during human development.

The cricoid cartilages connect the cricoid bone and the larynx, and are connected to the arytenoid body by ligaments. The larynx is a complex structure, and it moves relative to the hyoid bone. The larynx also extends vertically, from the epiglottis to the border of the cricoid cartilage, which marks the formal beginning of the trachea.

The larynx is surrounded by a mucus-filled membrane. When swallowing, the larynx folds over to cover the vocal cords. The cuneiform and corniculate cartilages sit on top of the arytenoid cartilage. When a person coughs, these cuneiform cartilages close off the throat to keep air from entering the lungs.

Epiglottis

You may wonder how to build an epiglottis. The epiglottis is a cartilaginous flap that covers the opening of the pharynx during swallowing. It attaches to the hyoid bone and thyroid cartilage. It also attaches to the posterior aspect of the tongue. As you swallow, the epiglottis closes and tilts posteriorly to direct food to the larynx.

Historically, people with epiglottitis were infected with the Haemophilus influenzae type B bacteria, which cause many serious diseases. In developed countries, Hib is less common because children have been immunized against the infection. However, you can still harbor the bacteria in your epiglottis without getting sick. You can also develop epiglottitis from physical trauma, including drinking hot or caustic liquids.

If your child has this problem, they may feel a loud, gurgling, or even a whistling noise when they breathe. To alleviate the problem, they may be more likely to sit up or lean forward, with their tongue protruding. This will help open the airway and reduce the risk of a seizure. They may also be pale or gray, and their condition can lead to a collapse and even death.

Developing an exercise routine that strengthens the larynx and prevents food particles from entering the windpipe can improve your health and improve your ability to swallow. You can even learn a technique to swallow that helps patients with their epiglottis recover and prevent the risk of aspiration. If you are not able to swallow food, try to make the airway as wide as possible. This will make it easier for your larynx to open again and prevent aspiration.

Right recurrent laryngeal nerve

The recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) innervates the larynx. It branches off from the vagus nerve near the heart, loops around the aorta, and travels back up the neck to innervate the larynx. However, it isn’t always possible to find a RLN in humans. Some researchers think that the RLN is an “inferior” design.

The RLN originates in the caudal region of the brainstem, and travels dorsally down the trachea before splitting off from the vagus. Both sides of the RLN take different routes, and each has its own unique branch point. Both nerves innervate laryngeal derivatives. This is why they are often called recurrent laryngeal nerves.

Tumors can compress the RLN and lead to hoarseness in patients with lung cancer. Most of these cases are left-sided, and the presence of a tumor near the RLN is associated with worse outcomes. Tumors involving the recurrent laryngeal nerve may require surgical intervention. Additionally, malignant lymph nodes can invade the area that carries the ascending nerve.

Another anatomical variation affecting a RLN is the aortic arch. This is not a rare phenomenon, but it does occur in about 1% of people. On the right side of the chest, the RLN follows the aortic arch, while it is less often on the left side. The RLN also performs a sensory function.

In a patient with a recurrent RLN, the recurrent laryngeal nerve will usually branch more than the left one. There are several different RLN branching patterns, including type IV and type V. Most operations involve Type I RLN branching. The right side has a higher rate of Type III branches than the left side. Several of these nerves may be found on the left side.

CT stretching muscle

The CT muscle is the connecting piece between the two main cartilages that hold the vocal folds. When these folds lengthen or thin, the CT muscle contracts, stretching the vocal cords. This stretching increases the amount of tension in the vocal ligament, which in turn changes the pitch of the voice. While new singers may think that the longer vocal cords mean lower notes, the opposite is true.

The CT muscle is not visible on endoscopy, but it is attached to the cricoid cartilage and thyroid. By stretching it, the true cords lengthen and pitch increases during phonation. The photos show the muscle stretching during the most open phase of vibration. Because this muscle is attached to the cricoid cartilage, they cannot be directly seen during endoscopy. However, acoustic and psychological approach can help the muscle work in coordination with the other muscles in the vocal folds.

The muscles surrounding the larynx are called extrinsic. These muscles surround the larynx and give the head a range of motion. These muscles also stabilize the larynx during phonation. This helps to produce a loud and clear voice. This stretching exercise will help to develop the larynx. But be careful when stretching the muscles in the larynx, because some will overextend themselves.

The larynx is a complex structure that serves several important functions. It contains two sets of muscles, the external and internal. The external laryngeal muscles adduct the larynx while the internal larynx muscle moves the individual components of the larynx. These muscles are vascular and innervated, so they are important for breathing. When used in conjunction with stretching exercises, they can help the larynx build the voice.

About The Author

Pat Rowse is a thinker. He loves delving into Twitter to find the latest scholarly debates and then analyzing them from every possible perspective. He's an introvert who really enjoys spending time alone reading about history and influential people. Pat also has a deep love of the internet and all things digital; she considers himself an amateur internet maven. When he's not buried in a book or online, he can be found hardcore analyzing anything and everything that comes his way.